Up the Gatineau! Article

This article was first published in Up the Gatineau! Volume 18.

Simmons General Store — 1884-1926

Nancy and Janet Benedict

This account was compiled by Mrs. Nancy Pearl {Simmons} Benedict, daughter of Alonzo and Jennie Simmons. After her death on December 25, I985, additions and updating were provided by her daughter, Janet Benedict in 1988.

With the passing of time and numerous changes, the name and location of Simmons, Quebec, may not be familiar to some, although it still appears on official maps in the north-east sector of Aylmer.

The Simmons family farm was located on Lot 16 in Range 5, Township of Hull, on the easterly side of the Simmons-Moffatt Road (now Vanier Road) between Pink and Cook Roads. Benjamin Alonzo Simmons III was educated and farmed his parents‘ farm here prior to 1884, at which time he suffered a serious injury and could no longer farm. After taking a business course, he purchased one acre of property from his parents‘ farm and had a two-storey frame house built in 1884. As he saw the need for a general store in this locality which was eight miles from any other store, he made the front room on the south side of the first floor into the “Simmons General Store".

The other front room along with the room at the rear of his house became his living quarters, along with two bedrooms upstairs. Across the driveway, to the south of his house, he had a long frame shed erected, which served numerous purposes. The section directly across from the store at the west end was the storage for drums of oil, heavy rope, and binder-twine. The next section was used for stabling the store's horses, and also had a place for the buggy and cutter. The granary was next, and the last section was for livestock feed.

The store quickly became a very active business, in fact, the owner found it difficult to meet the demands.

He carried a large variety of items to serve the farming community. In 1884 some of the prices and items were: barrel of salt pork $19.00, barrel of flour $7.00, bag of beans $4.00, l lb. sugar 5¢, 55-lb. chest of tea $22.00 or 1 lb. of tea 35¢, l lb. tobacco 50¢, pr. boots $1.65, a pair of leather mitts $1.25, pr. of blankets $5.35, hand towel 9¢, pail 22¢, heavy axe $1.30, axe handle 20¢, 4 bolts 10¢, 1/4 lb. rivets 15¢, scythe hook 25¢, 2 pr. bridle bits 20¢, bottle of spavin cure for horses $1.00, and a large wooden box of matches 25¢.

The gross income for farmers at this time was less than $300.00 per year. Wages for shanty men who worked 10-12 hours a day were $16 per month; if they took a team of horses, they were allowed $10 extra. In 1886 rural school teachers were paid $80 to $100 annually to teach 25 to 30 pupils from grades 1 to 6 in a sparely furnished one-room school, while a boy who lit the fire for the winter received $4.00. One-way train fare from Aylmer to Ottawa was 25¢.

On June 6, 1894, Benjamin Alonzo Simmons married Mary Jane Radmore of Eardley, Quebec. This very hospitable couple soon became known as “Aunt Jennie" and “Uncle Alonzo". Over the years they had a family of seven: William (1894-1974), Percy (1896-1972), Nancy (Mrs. Clayton Benedict) (1899-1985), Edward (1901-1971), Harold (1903-1981), Florence (Mrs. Lloyd Macdonald) (1905-1976) and Fanny who died in infancy. As the children grew up, they all assisted in the store.

Alonzo had a large timber erected through the roof of the granary, with a windmill on top for power. In the evening after the store was closed, he would grind oats, barley, wheat and corn into feed to sell in the store. He also did custom grinding. Around 1907 there was a bad electrical storm and lightning hit the timber. The windmill was destroyed and never replaced.

By this time the store in a growing community served quite a large area, from Hull on the east, Aylmer on the south, Eardley on the west and Chelsea on the north. Residents in Deschenes were also requesting delivery of groceries, hardware, etc. To this Alonzo agreed, and so until 1923 he went there every Friday morning with their deliveries, and at the same time took orders for the following week. On his return trip, he brought back a load of flour and feed from the mill at Deschênes.

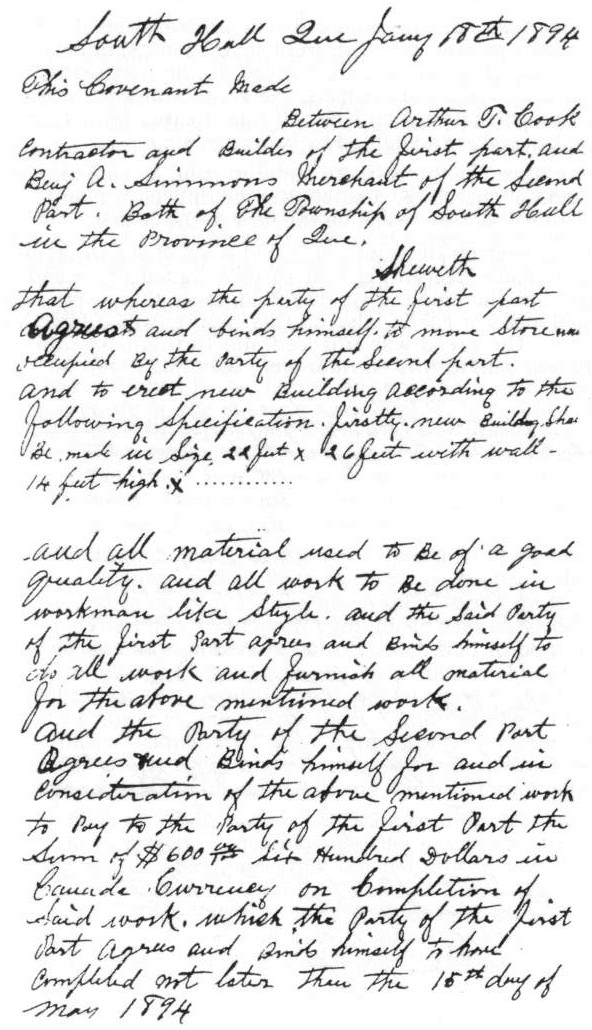

To meet these growing business needs, Alonzo expanded the store. In 1894, a contract was given to Arthur Cook I to move the original building back easterly and build a larger two-storey frame house on its site. The new building had three bedrooms and was attached to the previous house, which was then to be used as their residence with its own private entrance.

This new building was fully described in the contract, with the house of clapboard, the roof cedar shingled, and rooms to be finished “with lath and plaster 2 coats each, each room to have one window and one door. “Furthermore,“ all material used (was) to be of a good quality and all work to be done in workman like style".

The first floor on the front of the house was used for the store and the sign erected over the front door read “Simmons General Store". A row of tall spruce trees stood on the north side, and the entrance door and windows faced the south and west. It was quite bright and attractively laid out. It was heated by a large wood burning box stove, and lighted by kerosene lamps.

There were two fifteen-foot counters, running east and west on either side of the store, also shelves behind both counters. full-length, from about three feet off the floor to the ceiling.

The counter on the south side had a set of scales, as in those days practically everything had to be weighed or measured for whatever specific amount was required, since there were no ready packaged foods or goods. Also on this counter was a large built-in bread box. The bread was unsliced and furthermore unwrapped. The shelves behind this counter were piled high with all kinds of groceries, canned goods such as fruits, vegetables and salmon.

The upper shelves were reserved for an assortment of patent medicines and various aids used in home doctoring such as liniments for the relief of pain or swelling in man or beast, large bottles of Burdock Blood Bitter and Pain Killer (which was a must in every home), Pink Pills for Pale People, Dodd‘s Kidney Pills and Carter's Little Liver Pills. Sulphur and Epsom salts were always in plentiful supply, along with numerous livestock remedies. Then there were various styles of kerosene lamps and lanterns, also the different sizes of globes for them. Of course candy was displayed in large glass bottles on the lower shelves. The children's chief attractions were the 1-a-penny and sugar stick candies. Underneath these shelves were barrels of sugar, flour, rolled oats, dried peas and beans, corn meal, and rice.

On the shelves behind the other counter were babies‘ boots, ladies‘ high buttoned boots, ladies’ hosiery 25¢ a pair, men's fine shoes, and entire outfits of men's work clothes, including footwear. Work socks were 25¢ a pair, fine shirts were 50¢ and 75¢, with separate white shirt collars. There were piles of wheeling yarn in 4-oz. skeins in which there were several colours, mostly red, gray and white. As the era of the spinning wheel was just about gone, this yarn was purchased from an Ottawa wholesaler.

When fall came there were piles of hand knitting, including various sizes of mitts and socks from children's to men's sizes, knit by Jennie and later by her daughter Nancy. Men's mitts sold for 25¢ a pair. The linen and cotton yard goods they carried came in bundles of various numbers of yards, which had to be rolled into webs for the shelves. These were mostly prints in shades of blue, green and brown. A measuring stick was fastened to the top, outer edge of the counter for measuring them. Cotton print sold for 10¢ a yard and pillow ticking 25¢ a yard. Large quilt batts were 50¢. The store carried nearly every line of sewing and needlework supplies and a large selection of household linens was also found here.

At the back of the store, level with the counter, were sectioned boxes for the numerous and various smaller pieces and items in the hardware line, including sad irons {heated on the wood stove for pressing or ironing cloths). Barrels which had been emptied earlier of food supplies were used for holding brooms, hand-made mops, garden forks, and shovel and axe handles. They also stocked a couple of kinds of shovels, spades, hoes, 3- and 4-proriged forks, axes and rakes.

They carried a full line of school supplies, including textbooks, slates, pencils, erasers, etc., as well as stationery items. There were also a few clay pipes at 5¢ each, a case of wooden pipes selling at 25¢ each, along with shag, plug and chewing tobacco. The barter system was used somewhat by farmer customers who offered eggs, butter, oats, fowl and various other farm products in exchange for groceries, dress goods, hardware, wood, etc.

Country children of the time walked long distances to school to obtain the little education that was available in the 1880s and 1890s. There was no compulsory school attendance law and no family allowance to ease the financial burden. Many children, due to pressure of the necessary work at home, could only attend when work at home permitted, which was usually only in the winter time. The Simmons family was no exception.

In the cellar was a barrel which contained some lye {made from wood ash) and during the winter fat drippings and grease were put in it. On the first fine spring day, Jennie would be outside making soap from the mixture, which had to be blended carefully without using too much lye. Again, some of this soap was sold in their store.

Alonzo always saw to it that there was a plentiful supply of groceries, salt pork, codfish, and lots of hand-knitting and leather mitts ready for the men from the community to pick up at the first fall of snow as they left for their wood lots on the mountain.

By 1896 some of the prices were: 1 lb. of butter for 20¢, fresh eggs 13-15¢ a dozen, buttermilk from the farmer for 51¢ a quart, tomatoes 10¢ gal., corn 7¢ a dozen, bag of turnips 20-30¢, a gallon of ripe beans 10-15¢, a bag of carrots 25-30¢, a bag of beets 25-30¢, a dressed chicken 30-50¢, and native tobacco 10-12¢ per lb.

In the early 1900s each taxpayer, besides paying taxes also had to do a day's work for every 50 feet of frontage bordering a public road.

By 1900, in order to keep his well-kept and groomed team of horses on the road for all weather conditions, it would have cost Alonzo $2.40 to have a set of 8 shoes put on, while to trim a hoof, reset and replace a shoe was 15¢ per hoof.

In 1905 Alonzo and Jennie purchased an adjoining 49 acres of land from his mother. He rented part of it (a cow put out on rented pasture brought in $2.00 per month) while the remainder was kept for a garden in which he grew potatoes, turnip, rhubarb, etc., which he sold and delivered with his grocery orders. A little later he had the opportunity to purchase an additional 50 acres adjoining his property; consequently, he purchased more cattle, and a team of draft horses and farm machinery as he could sell all the butter, cream, buttermilk and eggs (now 25¢ a dozen) that he had to spare.

In the early pan of the 19th century, a mica mine opened on Morris Road (on the mountain and near Pink Lake). This meant further good customers, as they purchased not only their groceries, but also all their work clothes. As there were no bread deliveries in those days, Jennie baked all their bread and pastries, which were delivered to them once a week.

Some of the prices and items in the 1900s were: tea, mostly green and Japan in 20 and 40 lb. chests selling for 15¢ and 25¢ a lb., soda in 20-lb. boxes, vinegar in approximately 60-gal. barrels, lump laundry starch in wooden trunks 10" x 8" x 8" high with a latch on the lid, and dried evaporated apples in 50-lb. boxes. Raisins in 25-lb. boxes were not seeded, so we had a raisin seeder. Currants came loose in 50-lb. boxes, which had to be picked over (for stems, etc.); coarse salt was in 100- and 140-lb. bags, fine salt in 50-lb. bags. Sugar came in 100-lb. white cotton bags and sold at 10 lb. for 25¢; sweet biscuit in 1O-lb. boxes sold for 10¢ 1b., molasses came by the hogshead (2 barrels) about 100 gal., artificial maple syrup in 5-gal. tins, corn syrup in 5-, 10-, and 20-lb. tins, caramel candy in tubs 18" across and 8" deep, hard candy in pails 18" high x 18" across the top and 12" across the bottom, and stick candy at 1¢ each.

Jennie churned and made butter in the summer, and packed it in earthen jars which were tightly covered with foil (from the tea chests). It was used during the winter when milk production was down; likewise she also packed eggs in coarse salt in wooden boxes during the summer when they were plentiful, for winter use for baking purposes. In the fall after the butchering of hogs was done, Jennie also packed pork in a salt brine in the thoroughly scrubbed wooden barrels. Most farmers had their own beef, and some raised pigs so had their own pork. Barrels of salt pork were also purchased the year around. In the winter salt herring and smoked cod fillets were also available.

The store carried practically anything a person could name in the hardware line, such as turpentine, oils, paints and brushes. It had all laundry supplies, all kinds and sizes of cooking and baking utensils (a lot were made of iron) and steel cutlery usually with black wooden handles. Kerosene came in steel drums and was measured out in demijohns; customers usually purchased 5 gallons at a time.

Practically all kinds of carpenters‘ tools were kept, including all kinds and sizes of nails, bolts, nuts, screws and bits; spoke shaves, pinch bars, post hole augurs, a variety of hand saws, and claw and round head hammers. For the hunters the store carried a supply of gun cartridges, pistols and caps. For men who did bush work and lumbering, there were cross cut saws, horseshoe nails, horse whips, halters, bits and, of course, jack knives.

In the gardening line they carried all the tools needed, also seeds and potato bug poison. For haying and harvesting they had forks, scythes, cycles and binder twine which came in 3 qualities in 50 lb. bales. Farmers were not forgotten as the store carried all kinds of milking equipment including cream cans, cow chains, a variety of sizes of ropes and chains, whet and emery stones, kegs of square and round nails, barb and page wire, wire stretchers and staples, files and ice tongs. They had numerous kinds of livestock feeds, for which they had a large platform scale for weighing same, as well as a hand truck for loading and unloading these heavy items.

Especially for the Festive Season they carried a good supply of dolls, toys and Christmas stockings.

Every fall Alonzo purchased a flat truck of hardware items and groceries. The wholesalers at which he dealt gave him premiums, especially with the extra-large orders. The premiums included a Family Record, a small scale weighing up to 4 lbs. and an aluminum scoop. These last two items were used extensively in the store.

In 1916 some items and the prices they were selling for were: cornflakes 11¢ pkg., smoked fillets 15¢ 1b., fresh sole or cod 6¢ 1b., bar maple sugar 14¢, 1 lb. candy 20¢, box Spearmint gum 85¢, pkg. Rex tobacco 9¢. Derby cigarettes 51¢, box cigars 10¢, 1 dozen men's hankies $1.50, socks 35¢ a pair, a good brand of boots $10.00, girls‘ patent leather shoes $2.50, women's oxfords $4.75. A man's suit could be bought for $25.00 and there were several colours to choose from; a pincushion was 15¢, lace was 2 1/2¢ yd., yard goods 20¢ yd., cambric 10¢ yd. At that time the Ottawa Evening Citizen sold for 3¢, a hired farm hand received 50¢ to $1.00 for a day's labour, and a clerk in a general store got $9.00 a week in wages.

In the very early 1920s the milk they handled was required to be cooled with ice. This had to be cut and drawn from a nearby lake or river, and sawdust had to be purchased and drawn from a sawmill to pack the ice to preserve it from the summer heat.

In 1925, for $7.69 a person could purchase an order consisting of coffee, butter, eggs, bacon, flour, lard and baiting powder. At this time 6 lemons sold for 18¢, a gallon of apples 35¢, cheese 45¢, 5 lb. sugar 45¢, fresh eggs 50¢ doz., 1 qt. milk 6¢, 1 lb. bacon 25¢, cottage ham 95¢, codfish 25¢, peanut butter 20¢, loaf of bread 10¢, and Salada tea 75¢. While in season, a quart of strawberries cost 25¢, and 1 lb. tomatoes 5¢. A large package of cigarettes was 35¢, 2 bars of Sunlight soap 15¢, Rinso soap (powdered) 25¢, Palmolive soap 25¢, Lifebuoy soap 10¢, floor wax 85¢, stove pipe — 18¢ per length, a 5-string broom 75¢, pocket knife 15¢. At that time a cup of coffee cost 10¢, a hot-dog was 10¢, and a ticket to a picture show 20¢.

A bench near the stove in the store provided a place, especially on Saturday nights, where men, young and old, came and local news was accumulated and despatched freely, from weather and crops to the new school teacher and politics. Many a joke was also told. However such news was limited mostly to hearsay. For outside news the residents had to rely on the printed word, but very few received a paper of any kind, much less a daily. If a death occurred in the vicinity, a small white card edged in black with the information on it was available at the store for people to take for themselves or pass on to others.

As midnight drew near, Jennie would make a cup of tea for these folk, (which sometimes included women who had come to shop) while one or two of the men would buy a box of goodies, to share with the rest. Then all would depart for home. The store was closed on Saturday night, not to open again until 6 a.m. on Monday.

Alonzo and Jennie didn't enjoy much of a social life apart from the store and community affairs. They were both noted for being active members of Mountain View Methodist Church, and figured prominently in its building, as well as in the re-building of Simmons School #2 after a fire in 1870. Both of these buildings were on Benjamin Alonzo Simmons I‘s land holdings. Alonzo assisted in auditing the municipal and school books, for which he received $5.00, whether it took him one day or one week. He was also toll gate keeper at the Gatineau County Agricultural Society Fairs in Aylmer for numerous years, and a member of Dundonald Loyal Orange Lodge 1912, and of the independent Order of Foresters.

Very early in 1925, shortly after Alonzo's 67th birthday, he took suddenly and seriously ill and died. His wife and two daughters then took charge of the store, and in 1926, as Nancy was planning to marry, the Simmons Store was closed and its contents sold to Mr. and Mrs. Sifton P. McClelland and relocated. Harold Simmons, the youngest son of Jennie and Alonzo, inherited the property. Jennie spent her last years with her daughter and son-in-law (Nancy and Clayton Benedict) who lived on Iron Mine Road (now Cite des Jeunes Blvd.) in South Hull. Jennie died in the fall of 1943, aged '78 years and was laid to rest beside her husband in Pink Cemetery.

The following verse was written by Nancy about the store:

“A little of everything for simple needs

A meeting place where everyone knew each other

An exchange of local gossip and news

A vanishing souvenir of yesteryear.”